a study by Maggi Rohde

Anne Hoey

and Pamela Chamberlain

SI 666 Fall 1998

Introduction

Young adults are often thought to be underserved by public libraries.

Only 37% of all public libraries employ a librarian targeted at

serving both young adults and children, and only 11% have a young

adult librarian (Heaviside et al, 1995). This implies that a minority

of public libraries spend significant money or time on improving

services for young adults. Conversely, many librarians believe young

adults don’t take advantage of library services because of

competition from other, more attractive activities. Thus, to increase

YA involvement in libraries, the best course of action would seem to

be to make the YA collection as accessible and easy to use as

possible, without adding to the burden of existing staff or budget.

One way to do this is to organize the YA fiction collection by

genre.

Both early and recent studies on arranging fiction collections by

genre indicate that this type of arrangement both increases

circulation of books and is preferable to a majority of

patrons:

• In the only fiction classification study done on young adults, in a

junior high school library in California, 88% of students found the

classed system easier to use than the previous alphabetically-

arranged system (Briggs, 1973).

• The earliest study was done in 1902, in which a portion of a public

library collection was shelved by genre and circulation patterns

studied for two years. After the rearrangement, 57% of circulated

books came from the genre-arranged fiction, a significant increase

(Borden, 1902).

• One British study done in public libraries reports that 59% liked

having the fiction collection classed and shelved according to

genre, while only 24% wanted it classed and shelved alphabetically

(Spiller, 1980).

• In another British study, 79% of adult fiction readers preferred

having the fiction classed and displayed separately (Ainley and

Totterdell, 1982).

• After writing a review of all aformentioned studies on fiction

classification, Sharon Baker performed her own study on public

libraries, in which she found that separating fiction into classed

categories does increase circulation, by as much as 98% (Baker,

1988).

From this evidence it seems reasonable to hypothesize that:

• Arranging YA fiction by genre on the shelves will increase

circulation of those items, and

• YA patrons will prefer this arrangement to the previous one

(alphabetical by author).

The primary goal of our study was to test this

hypothesis.

Our study followed this course:

1. Create an organizational scheme that is appropriate for YA

fiction collections, based on existing studies.

2. Implement this scheme on a small scale in a public library in order

to test the hypothesis.

3. Evaluate effectiveness, usability and practicality of scheme based

on patron feedback, completed surveys and circulation data from the

public library.

Creation of an Organizational

Scheme

Before consulting the literature, we first sent a message to the

professional YA librarian’s email list (YALSA-BK) to ask for

success stories from librarians who had arranged their own

collections by genre. The responses were encouraging. Kate McLean

from the Tucker-Reid H. Cofer Library in Georgia said “I loved

it! It is wonderful for browsing collections. During that summer

[when my collection was arranged in this way] I do believe

circulation grew; no stats though.” (McLean, personal

communication, 1998) Lesley Gadreau of Seabrook Library in New

Hampshire provided us with her set of nine categories, along with a

suggestion to use a “secondary sticker” on the spine of the

book to indicate crossovers in genre, such as romantic historical

fiction, or humorous fantasy. She indicated that rearranging her

collection into genres has helped her patrons choose new authors to

read, which is one of the three fundamental purposes of

genre-arranged fiction schemes:

“I rearranged my YA fiction collection about two years ago into genres and my circulation has more than tripled.... [T]he arrangement of the books by genre helped kids be more successful in finding books and in moving from books they knew they liked to new titles and authors. My faithful R.L. Stine readers started reading Duncan and Lovecraft and Nancy Drew fans gave other mysteries a try.... I don’t regret the reorganization one bit.” (Gaudreau, personal communication, 1998)

We also received pointers toward studies on

fiction classification, such as Sharon Baker’s research from the

late 80’s.

No definitive research has been done to determine the ideal set of

categories for use in designing a scheme for classification of

fiction, but there are some basic principles behind the success of

such schemes. Sapp has made mention of the fact that using the Dewey

decimal or Library of Congress classification schemes for fiction are

too limited and restrictive to be useful in targeting these

principles (Sapp, 1986), and thus they were not consulted when

creating our scheme.

As outlined by Baker in her review article on fiction classification

schemes, the three main points are:

1. Fiction classification should make it easier for library patrons to find the

types of books they want.

2. Patrons select books in many different ways, including genre,

broad subject, format and literary quality; classification schemes should

take these multiple methods into account.

3. Fiction classification should also expose the patron to new authors.

(Baker, 1997)

Thus, in accordance with point 1, our scheme

included enough categories to appropriately subdivide the collection,

but not so many as would confuse patrons. Categories were not

subdivided below one level, again, for ease of use. To help fulfil

point 2, categories included both genres (i.e. mysteries) and

subjects (sports, adventure). However, we agreed to shelve the

classics and graphic novels in with the contemporary paperbacks,

rather than creating separate categories for them, as this would seem

to increase the likelihood that patrons would read different formats

and qualities of books. Lastly, point 3 was addressed in the fact

that our organizational scheme would be presented as a collection of

fiction shelved by genre, rather than labeled and shelved

alphabetically, as this former method of presentation has been shown

to increase the patrons’ exposure to new authors (Spiller, 1980;

Borden, 1902; Baker, 1988).

To select a set of appropriate categories, we turned to textbooks for

YA librarians (Jones, 1998; Arnold, 1998). We also consulted with a

YA librarian at Canton Public Library, Wendy Woljter, as well as

several librarians in other states who have arranged their YA fiction

by genre. Eventually we settled on this set of nine

categories:

1. Adventure & Survival

2. Crises and Life Changes

3. Families & Friendships

4. Historical Fiction

5. Mystery & Thriller

6. Relationships

7. Science Fiction & Fantasy

8. Sports

9. Supernatural

This set was broad enough to encompass all the

fiction we wished to include in our study without resorting to the

vague “General Fiction” category. We also purposely chose

the name “Relationships” instead of “Romance” to

see if that would draw a larger audience, but as the results will

show, this was probably a poor choice. “Supernatural”

defined the category of realistic fiction with a twist, such as

vampire and ghost stories, but which were not targeted at scaring or

grossing-out readers. “Crises and Life Changes” included

themes like death, abuse, sucide, racial tension, and abortion.

Implementation of Chosen Scheme

After confirming our organizational scheme, we chose a set of books

to fit these categories. Our first choices were books which were less

than four years old and had been favorably reviewed by ALA,

Booklist or another source. We used lists which we found on

the ALA web site and in profesisonal journals, as well as drawing

from our personal experience with YA literature.

In order to test our hypothesis, we worked with actual circulating

collections of books, as well as using an online simulation. We

contacted three libraries with which we had familiar interactions:

the Canton Public Library, the Howell Carnegie District Library, and

Huron High School.

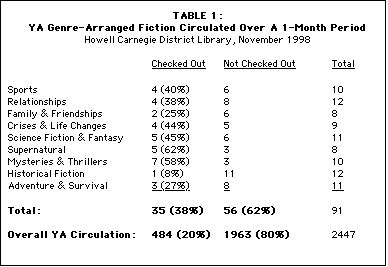

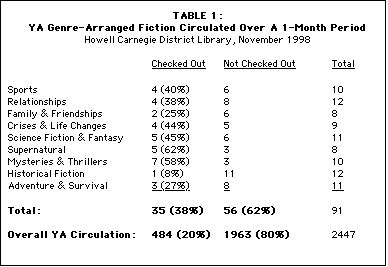

Real World Testing. The Youth Services Coordinator at Howell

Carnegie District Library, Holly Ward Lamb, agreed to allow us to

pull a subset of her YA fiction collection to display in a

genre-arranged format for one month. We chose all the fiction which

was present both on our list and in the Howell collection, and then

supplemented with additional appropriate titles from the collection.

We labeled a final set of 91 books with colored stickers, one color

for each category, and shelved the set under a small legend for the

categories. After one month, circulation data for the genre-arranged

fiction was collected and compared to the overall circulation of YA

fiction in the Howell YA collection. Results are summarized in Table

1.

Online: A Simulated Browsing

Environment. Because we

would not be able to set up a similar physical arrangement of

books

at other locations, we created a web page which would help us

simulate the browsing environment a patron might encounter at

the library. This presented the patron with a bookshelf of

color-coded

books, on which they could click and browse through the books by

subject, looking at the covers (scanned photos of the books) and

reading the dust jackets (short abstracts). This “web

bookshelf” was

used both at Canton Public Library and at Huron High School; the

media specialist at Huron, Gail Beaver, employed a more

controlled

environment by guiding two freshman classes to the web page and

asking them for feedback.

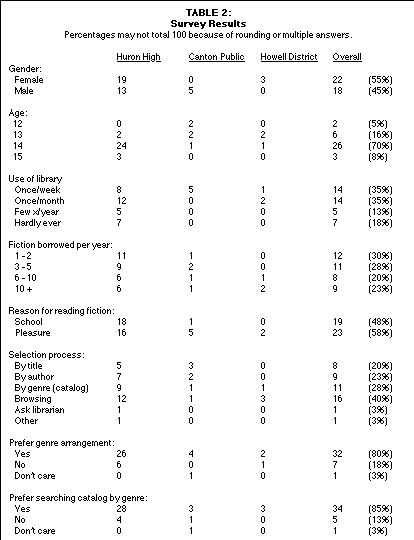

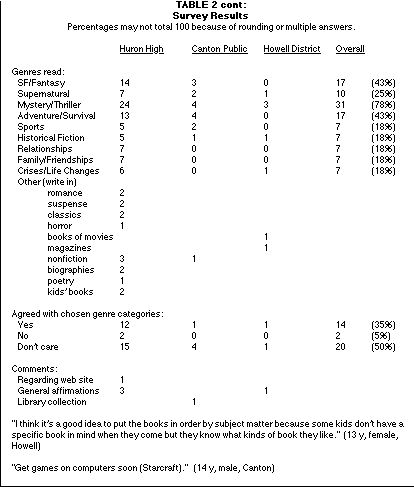

Both settings were provided with a one-page survey to solicit

feedback. At Howell and Canton, the surveys sat out for patrons to

fill out as they chose. In addition to basic demographics, the survey

asked the following questions (see Table 2 for a summary of survey

results from the forty surveys which were returned and usable):

• How much do you read? How often do you use the library? Do you

read for pleasure or for school?

• How do you most often find fiction books at the library?

• Do you want your library’s YA fiction arranged in genre format,

rather than by author?

• Would you like to be able to search the computer catalog by genre?

• What kinds of fiction books do you like? (offering choice of genres)

• Would you have chosen the same names/types of categories that we did?

• Other comments, etc.

Results and Evaluation

The hypothesis presented in this study had two aspects. First, that

arrangement of YA fiction by genre, shelved separately, will increase

circulation of these items; and second, that the patrons of the YA

fiction collection will find the genre-arranged fiction easier to use

and preferable to alphabetically-arranged collections. We find, by

examining both the surveys and circulation statistics at Howell

Carnegie District Library, that both aspects of the hypothesis are

supported by our data.

The Howell data provides support for the first aspect. The percentage

of circulation across the entire YA collection was 20%, while

circulation of genre-arranged items was 38%. This is not a large

enough sample or an extensive enough study to give any truly credible

data, but it does correlate with previous literature: arranging

fiction by genre increases circulation of those items.

Data from the surveys support the second aspect of our hypothesis.

According to the survey, 80% of respondents would prefer to have the

YA collection in their library arranged by genre, as opposed to 18%

who like it the way it is. This is consistent both across frequent

library users and those who “hardly ever” use the library.

Anecdotal data from incidental browsers of the collection at Howell

also indicates that YA’s find genre-arranged fiction much easier

to use.

One reason given in the literature for the preference for genre-classed fiction is that of information overload in large collections. Patrons browsing in a large library often feel overwhelmed by too many choices, and this leads to a difficulty in making selection decisions (Baker, 1998). Genre classification helps decrease this confusion. Baker ascribes information overload only to users of large collections, however; one study shows patrons in a library with 4,700 books did experience information overload, but not in one with 1,700 books. Another study found information overload in a library with 6,000 books, but not in one with 2,500.

Obviously the question of “how large is

large?” is difficult to answer when considering the effects of

information overload. While the YA collection studied here has fewer

than 2,500 items, the question of the skill and experience level of

the patrons in making selection decisions must be considered. Young

adults between the ages of 12 and 15 are not as skilled at making

choices as an adult, and therefore the possibility exists that they

may experience information overload at much lower stimulus levels

than adults. It should be pointed out, for example, that shelving YA

literature apart from adult literature significantly increases its

use in all public libraries, no matter what size the YA

collection is (Heaviside et al, 1995). Further study is necessary to

address the question of information overload in young adults.

When considering what we might have done

differently in the course of the study, we first examine the surveys.

The focus of the survey was to obtain data about our population and

generally whether they preferred the genre arrangement over

alphabetical arrangement of fiction, rather than on whether this

arrangement would actually cause them to check out more books. In

this case, we felt it was more accurate to let the circulation

statistics determine whether or not patrons would truly cause an

increase in circulation, and have the patrons only give feedback on

their personal preference for a browsing display. However, it would

have been useful to include some questions about whether or not

patrons experienced information overload when dealing with

undifferentiated collections.

The names for categories used in the classification scheme proved to

be a bit confusing for some patrons. A few girls asked “What

about romance?” without making the connection to

“Relationships” as encompassing romantic literature.

Similarly, some patrons asked for “suspense” or

“horror,” feeling that our categories of

“Supernatural” and “Mystery/Thriller” didn’t

cover all the bases. Were we to revise the classification scheme, we

would probably rename the categories using the more customary

categories used by booksellers. In addition, we might choose to

combine “Friends and Families” and “Crises and Life

Changes” into a single category of “Realistic Fiction”

to make it easier for the cataloger. Finally, determining the

difference between “Supernatural”, “Science Fiction

& Fantasy” and “Mystery/Thriller” might prove to

be too complicated, and two of those genres would probably be merged

in some way. Further studies regarding genre labels for YA’s is

definitely indicated.

Ainley, Patricia and Barry

Totterdell. Alternative Arrangement: New Approaches to Public

Library Stock (London: Assn. of Assistant Librarians, 1982).

Arnold, Mary. “ ‘I Want Another Book Like...’ Young

Adults and Genre Literature,” Young Adults and Public

Libraries, Mary Anne and C. Allen Nichols, eds. Connecticut:

Greenwood Press, 1998, p. 11-22.

Auerbach, Barbara. “Hangin’ at the Library,” School

Library Journal 42:60, Jun 1996.

Baker, Sharon L. and Gay W. Shepherd. “Will Fiction

Classification Schemes Increase Use?” RQ 28:366-376, Spr

1988.

Baker, Sharon L. “Fiction Classification Schemes: The Principles

behind Them and Their Success,” RQ 27: 245-51, Win

1987.

Borden, William A. “On Classifying Fiction,” Library

Journal 27:121-24, Mar 1902.

Briggs, Betty S. “A Case for Classified Fiction,”

Library Journal 98:3694, Dec 1973.

Heaviside, Sheila, Christina Dunn and Judi Carpenter. Services and

Resources for Children and Young Adults in Public Libraries.

National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of

Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, Aug

1995.

Gaudreau, Lesley. Personal communication, October 20, 1998.

Jones, Patrick. Connecting Young Adults and Libraries. New

York: Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc. 1998.

MacRae, Cathi Dunn. “The Secret Lives of Teenagers,”

VOYA 21:168-169 & 175, Aug 1998.

Marshall, Margaret. Libraries and Literature for Teenagers.

London: Trinity Press, 1975.

Maughan, Shannon. “YALSA and Booksellers: Building A

Bridge,” Publishers Weekly 245:31-32, Jun 1998.

McLean, Kate. Personal communication, October 22, 1998.

Sapp, Gregg. “The Levels of Access: Subject Approaches to

Fiction,” RQ 25: 488-97, Sum 1986.

Spiller, David. “The Provision of Fiction for Public

Libraries,” Journal of Librarianship 12:238-65, Oct

1980.